* This was originally posted on my old blog on January 7, 2011.

* 筆者の以前のブログに2011年1月7日付で投稿された記事の再掲です。

The Japanese-Language Proficiency Test (JLPT) now seems to be the de facto standard to measure the proficiency of students of Japanese as a foreign language. But as a native Japanese speaker who is frequently exposed to Japanese written and spoken by people from foreign countries, I do not place much trust in this test. Too often, the results of JLPT do not seem to reflect the actual Japanese skills of the examinees. This is particularly noticeable in students at the level of JLPT level 2 or 3 (New JLPT N2-4).

One of my friends is a JLPT level 2 holder. She hasn’t passed the level 1 (N1) yet, and I don’t know whether she wants to try taking it or not. Nevertheless, she sometimes works as a part-time translator and interpreter from/to Japanese and her native language, Russian. I once asked her how she can get those jobs without a certificate of a higher level of Japanese. She answered, “I just say ‘I passed the level 2 over five years ago.’ Then everyone assumes that my Japanese skills must be far beyond the level 1.”

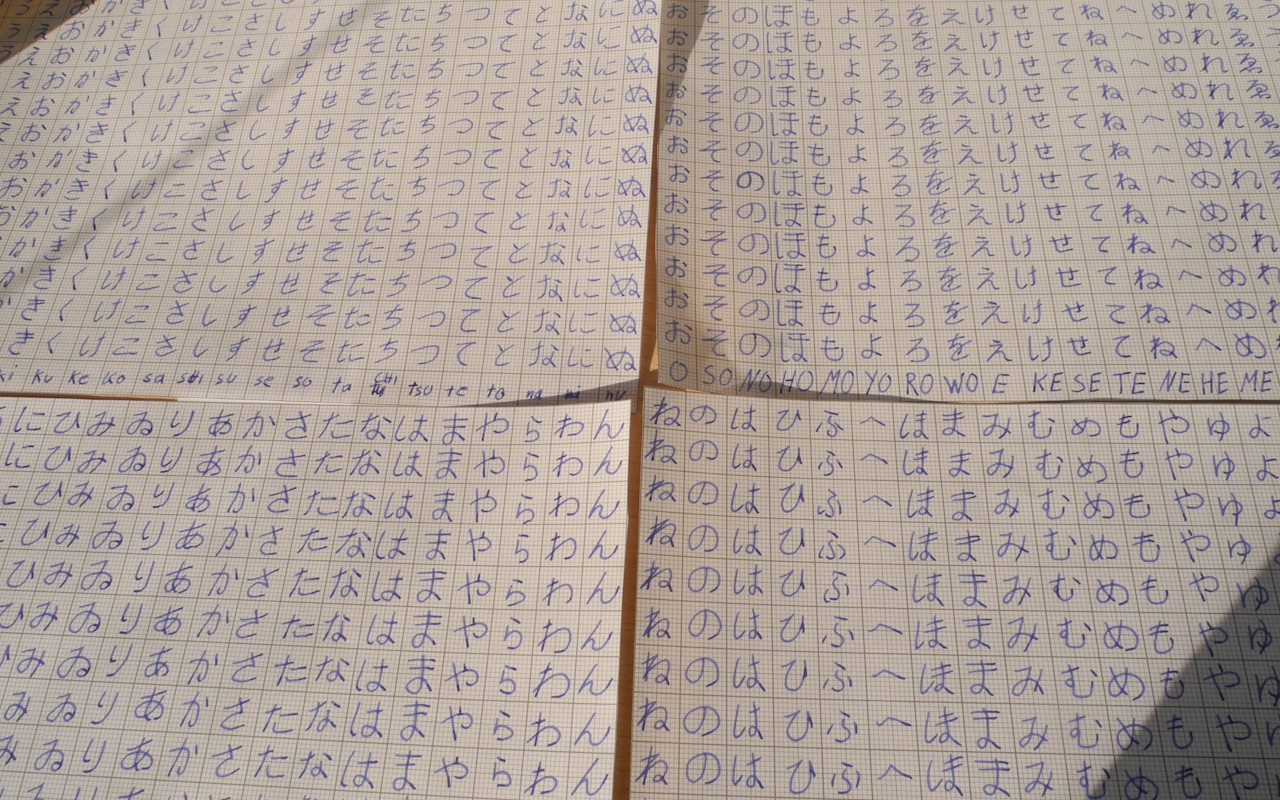

Honestly, even among people who are able to pass the level 1, the actual skill level can vary considerably. I have a non-native colleague who has lived in Japan for a long time. She passed the level 1 with a good score many years ago, but when I proof read her Japanese writing, more often than not, I have to ask her to explain what she wants to say in English. Also, her spoken Japanese sounds quite foreign even though it’s difficult to find any technical mistakes in it. On the other hand, another friend of mine, who is from Korea, has achieved amazing fluency in Japanese. I first met him at my graduate school, only four years after he came to Japan as a foreign student, but I thought he was a native speaker of Japanese until I noticed one day that some kanji characters he wrote looked a bit distorted. I was very much surprised when I learned that he had never studied Japanese before his coming to Japan. But anyway, the system of the JLPT classified both of those friends of mine as “level 1.” After all, JLPT evaluates primarily listening and reading comprehension skills. Speaking and writing are tested only indirectly.

Fortunately, Japanese people who study English have more options. There are at least three major English-proficiency tests that you can take in Japan: the Eiken Test in Practical English Proficiency (STEP Eiken), Test of English as a Foreign Language (TOEFL) and Test of English for International Communication (TOEIC). The latter two are given around the world. STEP Eiken includes a speaking test and handwritten composition component in addition to reading and listening. TOEFL, which is designed to test the language proficiency of non-natives who intend to study in the American university system, also consists of reading, listening, speaking and writing. However, the current standard test in the business environment in Japan is TOEIC, which usually has no speaking and writing sections. (There is a separate test called TOEIC SW, but that is not very popular yet.)

I have taken TOEIC only twice. The first time was when I was a university student, and my score was 830 out of 990. Not excellent, but not bad either. The second time was about three years ago, and at that point, I lost my trust in TOEIC. I got 970 and beat the scores of most people I know who can communicate in English far better than I can. My feeling may have been a little bit similar to the famous old complaint: “I would never want to belong to any club that would have someone like me for a member.”

Statistically, it must be true that those who show better performance in tests have greater proficiency in reality. I have no doubt about that. But it is extremely difficult to evaluate the language skills of each individual.